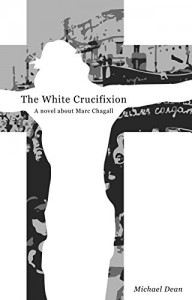

An inside look into the early life and creative process of Marc Chagall that goes well beyond a standard biography.

I received an ARC copy of this novel from the publisher, and I freely chose to review it.

Although I am not sure I would say I’m a big fan of Chagall's paintings, I’ve always been intrigued by them and drawn to them, even when I didn’t know much about the author or what was behind them. I’ve seen several exhibitions of his work and have also visited the wonderful Chagall National Museum in Nice, France (I recommend it to anybody wishing to learn more about the painter and his works, particularly those with a religious focus). When I was offered the opportunity to read this novel, written by an author with a particular affinity for the art-world, it was an opportunity too good to miss.

The book is not a full biography. It follows Marc Chagall (born Moyshe Shagal) from his birth in the pre-revolutionary Russian town of Vitebsk (now in Belarus) until he paints the White Crucifixion of the title. We accompany Chagall through his childhood (hard and difficult conditions, but not for lack of affection or care), his early studies and his interactions with his peers (many of whom became well-known artists in their own right), his love story with Bella (fraught as it was at times), his first stay in Paris, in the Hive (a fabulous-sounding place, and a glorious and chaotic Petri dish where many great artists, especially from Jewish origin, lived and created), his return to Russia and his encounter with the Russian revolution (full of hopes and ideals for a better future at first, hopes and ideals that are soon trashed by the brutality of the new regime), and finally his escape and return to France.

Throughout it all, we learn about his passion for painting, his creative self-assurance and fascination for Jewish life and traditions, his peculiar creative methods and routine (he wears makeup to paint and prefers to paint at night), his visitations by the prophet Elijah and how that is reflected in his paintings, his pettiness and jealousy (he is forever suspicious of other pupils and fellow painters, of his wife and her friends), and how he can be truly oblivious to practical matters and always depends on others to manage the everyday details of life (like food, money, etc.). He is surrounded by tragedy and disaster (from the death of his young sister to the many deaths caused by the destruction of Vitebsk at the hands of the revolutionaries) although he is lucky in comparison to many of his contemporaries, and lived to a very ripe old age.

The book is a fictionalization of the early years of Marc Chagall’s life (with a very brief mention of his end), but it is backed up by a good deal of research that is seamlessly threaded into the story. We read about the art movements of the time and Chagall’s opinion of them, about other famous painters (I love the portrayal of Modigliani, a favourite among all his peers), about the historical events of the time, all from a unique perspective, that of the self-absorbed Chagall. He is not a particularly sympathetic character. Despite his protestations of love, he is more interested in painting than in his wife and daughter, although he states that he feels guilty for some of the tragedies that happen to those around him, he pays little heed to them all and does not change his selfish behaviour, and he is far from modest (he feels he has nothing to learn from anybody, is clearly superior to most, if not all, his colleagues and he often talks about how attractive he is). He is unashamed and unapologetic, as he would have to be to succeed in the circumstances he had to live through. But, no matter what we might feel about the man, the book excels at explaining the genesis of some of his best-known early paintings, and all readers will leave with a better understanding of the man and his art.

The writing combines the first person narrative with the historical detail and loving descriptions of places and people, giving Chagall a unique and distinctive voice and turning him into a real person, with defects and qualities, with his pettiness and his peculiar sense of humour. Although we might not like him or fully understand him, we get to walk in his shoes and to share in his sense of wonder and in his urgency to create.

I wanted to share some quotations from the book, so you can get some sense of the style and decide if it suits your taste:

When I work, I feel as if my father and my mother are peering over my shoulder — and behind them Jews, millions of vanished Jews of yesterday and a thousand years ago. They are all in my paintings.

Here he talks about Modigliani and one of his lovers, Beatrice Hastings:

They had some of the most erudite fights in Paris. They used to fight in verse. He would yell Dante at her. She would scream back Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Milton, who Modi especially detested.

Modi once said ‘The human face is the supreme creation of nature. Paint it and you paint life.’

All my life I have blamed myself for whatever it was I was doing, but all my life I have gone on doing it.

So much for the revolution freeing the Jews from oppression. They had ended the ghettos, the Pales of Settlement, but the ghettos had at least afforded us a protective fence, of sorts, to huddle behind. Now we were like clucking chickens out in the open, waiting to be picked off one by one for counter-revolutionary activity.

As other reviewers have noted, the book will be enjoyed more fully if readers can access images of Chagall’s paintings and be able to check them as they are discussed. I only had access to the e-book version and I don’t know if the paper copies contain illustrations, but it would enhance the experience.

I recommend the book to art lovers, fans of Marc Chagall and painters of the period, people interested in that historical period, studious of the Russian Revolution interested in a different perspective, and people intrigued by Jewish life in pre- and early-revolutionary Russia. I have read great reviews about the author’s book on another painter, Hogarth, and I’ll be keeping track of his new books.

6

6