Anybody interested in post-WWII Germany and in Wolfe Frank should read this book.

I thank Rosie Croft from Pen & Sword for sending me an early hardback copy of this book that I freely chose to review.

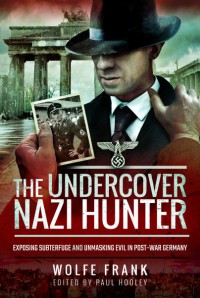

I have read and reviewed the fascinating Nuremberg’s Voice of Doom: The Autobiography of the Chief Interpreter at History’s Greatest Trials by Wolfe Frank ( you can check my review here) and when I heard there was a second book about Frank, centred on a series of articles about post-war Germany he wrote for the New York Herald Tribune, I had to read it as well. This book is also fascinating, but I missed more of Frank’s own voice, which made the previous book so distinctive and impossible to put down. On the other hand, I appreciated the work of the editor, who does a great job of providing background and trying to tie up loose ends.

The book includes several distinct parts. First, the preparation and background to the project. Although everybody seemed interested, getting everything in place in such a complex operation, as Frank was going undercover and there were many logistical complications to sort out — we must remember Germany was divided up into four zones under the control of different countries following the war. This part includes letters and documents of the time, and beyond its interest for Frank’s biography, it also provides a good insight into how newspapers and news organizations and syndication worked at the time. The editor also provides a good background into Frank’s personal history and his biography, which will be familiar to people who have read the previous book but means those who have not will easily get a sense of who Frank was and how he came about the project.

The second part is the articles as they were published at the time, The Hangover after Hitler series. Having read the previous book, it is clear that the articles were heavily edited, and Frank was writing under clear instructions. One cannot help but wonder what he would have written otherwise, but they are interesting as documents, not only of what was happening in Germany at the time, but also of what other countries wanted to know about Germany (mostly the USA), and how the different zones of post-WWII Germany were like. It sounds as if the different countries had completely different approaches to rebuilding and reorganising post-war Germany, and although we are all aware of what happened in the case of the Russian part, I had little idea of this in regard to the other regions before I read this book.

The third part is the confession of SS-Gruppenführer Waldermar Wappenhans, the SS General Frank discovered was still living in Germany after the war, in the British section of Germany, working for the British and living under a false identity. This is one of the most interesting sections of the book, and although the editor gives his own thoughts about it in the fourth part (and it makes perfect sense to think that Frank had a lot of influence in the way the “confession” was written), this man, who fought in both, WWI and WWII, and who in the confession comes across as somebody who never questioned his duty or what he had to do, and whose main interest was to go back to active duty (despite being repeatedly wounded) because that is what true men were supposed to do, provides an account of campaigns, weaponry, and also of agreements and disagreements between the different factions and actors that will delight anybody interested in the history of the period. He does not go into a lot of detail about his personal relationships or even his own reactions (although there are some light biographical moments, some that would horrify us [he casually recounts buying a young girl, with some other officers, in Haifa], some he seems to quickly skip by) and he depicts himself as somebody who speaks his mind no matter what, often resulting in his being moved and transferred to more risky posts. (I agree with the editor, who in part four writes that Wappenhans’s testimony “is more the autobiography of a brave warrior who unquestioningly obeyed the orders of superiors than the ‘confession’ of a Nazi wanted in connection with war crimes” (p. 282).

Part four, the aftermath, was the part I enjoyed the most. Here, the editor explains what happened and how the identity of Wappenhans came to be revealed (it seems Der Spiegel got hold of the information and revealed it on the same day Frank’s article came out, and there are clues as to where they might have got the information from), and also talks about some of the people involved and mentioned in the text and what happened to them. He also asks if Frank was working for British Intelligence, and makes a good case for it (it sure would explain a few things), and there is a final conundrum as well, as there were some drawings that might or might not have been by James Thurber that turned up in the file with the articles and documents. Personally, I like the drawings.

I recommend this book to anybody interested in post-WWII Germany, in finding more about Wolfe Frank (yes, we need a movie about him), interested in Wappenhans himself, and also in the workings of international newspapers in the late 1940s. I missed more of Frank’s own words, and if anybody reads this book first, I recommend you check Nuremberg’s Voice of Doom. It is a must read.

5

5